Tutte le opere . . . divise in V. parti et di nuovo con somma accuratezza ristampate. (bound with) De vanitate consiliorum liber unus, in quo vanitas et veritas, rerum humanarum politicis & moralibus rationibus clare demonstratur & dialogice exhibetur; (bound with) Libri tres de origine urbium earum excellentia et augendi ratione quibus accesserunt Hippolyti a collibus incrementa urbium sive de causis magnitudinis urbium liber unus.

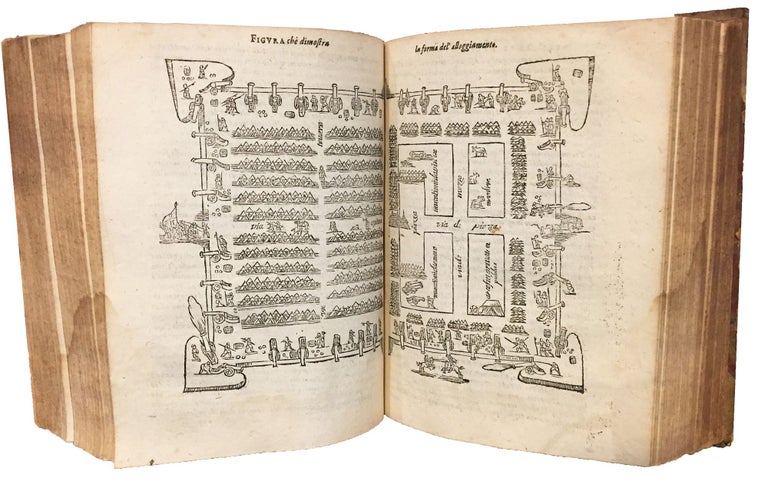

Florence: n.p., 1550 (1650); 1700; 1665. 7 books bound together (1st work in 5 parts). 4to. [viii], 320; 280; 152; 158; 106; 64; [vi], 234 pp. Edizione Testina. Vignette of Machiavelli’s portrait on title. Separate dated title pages to all parts except the Historie fiorentine which begins the volume. Dell’arte della guerra contains typographical figures depicting military formations and a double-page woodcut illustration depicting an army camp, and a manuscript table of contents following L’asino d’oro. Contemporary half vellum and marbled boards, manuscript titles on spine. Despite some browning and damp-staining, an excellent copy with an ownership inscription dated 1801 on the paste-down. Item #16016

I. Early edition of the political works of Machiavelli, which include:

--Gli otto libri delle Historie Fiorentine.

--Discorsi di Nicolo Machiavelli cittadino et secretario fiorentino, sopra la prima deca di T. Livio a Zanobi Buondelmonti et a Cosimo Rucellai.

--I sette libri dell’arte della guerra di Nicolo Machiavelli cittadino et secretario fiorentino.

--L’asino d’oro di Nicolo Machiavelli cittadino et secretario fiorentino, con tutte l’altre sue operette: La contenenza delle quali haurai nella seguente carta.

--Il principe di Nicolo Machiavelli al magnifico Lorenzo di Piero de Medici. La vita di Castruccio Castracani. Il modo che tenne il Duca Valentino per ammazzare Vitellozzo Vitelli, Oliveretto da Fermo, il signor Pargolo, & il Duca di Gravina. I ritratti delle cose di Francia & di Alemagna.

This particular publication is called the Edizione Testina, named after the author’s woodcut portrait on all the half-titles. Five variant editions are known, all showing 1550 as the (fictitious) year of printing on the title page, but which in reality are seventeenth-century forgeries. The Testina edition constitutes an interesting bibliographic case because of the particular difficulties of identification for the presence of variants, omissions and rearrangements. Machiavelli’s masterpiece, Il Principe, is the work with which he “founded the science of modern politics” by analyzing Cesare Borgia’s much-admired “mixture of audacity and prudence, cruelty and fraud, self-reliance and distrust of others” (PMM). Machiavelli firmly believes in the separation between politics and ethics, as each have different objects and goals. The term “Machiavellian” has come to mean a ruthlessness and immorality behavior in politics. He stated that total freedom from the religious power was the principle of a healthy State. The work was written in 1513 but was not published in Rome until 1532, five years after Machiavelli’s death. Il Principe exerted an enormous influence across disciplines and nations. The work soon became a practical examination of how “power” functioned. It was first placed on the Index of Prohibited Books, in the banned absolutely category, in 1559. The list of rulers who read and used the work is very long: “Henry III and Henry IV of France were carrying copies when they were murdered; Louis XIV used the book as ‘his favorite nightcap’; an annotated copy was found in Napoleon Bonaparte’s coach at Waterloo.”

Machiavelli (1469–1527) is known as the father of modern political theory. Born in Florence, he was a diplomat for 14 years in Italy’s Florentine Republic during the Medici family’s exile when the city was run by Girolamo Savonarola, a Dominican friar. No official records of Machiavelli’s life appear until 1498, immediately after the fall of Savonarola’s government, when he would have been 29. The Florentine Republic had been reinstated, and Machiavelli was appointed as secretary of the Second Chancery, a position in which he coordinated relations with Florence’s territorial possessions. As the “Florentine secretary,” he had opportunities to meet and observe many of the major political figures of the period. When the Medici family returned to power in 1512, Machiavelli was dismissed and briefly jailed.

II. First edition of a little known political work. Written in the form of a dialogue in twenty-five inquiries (Consultationes), in which Vanitas (Vanity) and Veritas (Truth) discuss issues concerning policy-making in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. A commentary on techniques of making correct political decisions, the author examines the notion of prudence or practical reason (prudentia) stemming from Cicero’s work. The third Consultatio of the work, De discordiis civilibus, et unione animorum (On discord between citizens, and on unanimity) is the most helpful passage to understand the author’s use of prudentia. Vanitas expresses concern about the dissent among citizens, while Veritas encourages to embrace it as long as it is viewed as the guiding principle of the world. Here we can see a similarity with Machiavelli’s Il Principe in asserting that a statesman’s duty is to find an appropriate means of using those very internal tensions for the advantage of his own goals as well as those of the state. Although this works contains both similarities and contrasts with Machiavelli’s thinking, it is very controversial due to its discrepancies at the point where Lubomirski describes the duties and characteristics of a ruler. It swings from being a pessimistic view of the political situation in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth to a commentary on techniques of making correct political decisions.

Lubomirski (1642-1702) was a Polish politician that fought in wars against Sweden and Hungary. In contrast to his father, Jerzy Sebastian Lubomirski (1616–1667), military commander and one of the most significant magnates of the seventeenth century, Stanislao was free of private ambitions and always acted according to the interests of the Republic. He was a prolific writer of poetry, plays, religious and historical treatises.

III: Scarce edition of a penetrating operetta in which the author deals with the legal and economic problems related to the birth of the modern city and state. Botero (1544–1617), an eminent economist and political theorist, joined the Jesuit Order in 1560 but left due to disagreements with his superiors. He became secretary to Cardinal Charles Borromeo, but in 1559 moved to Turin as tutor to the children of Charles Emmanuel of Savoy. A passionate reader of Machiavelli, he exposed his political views in his most famous work, Della Ragion di Stato (1598), the first to express the concept of the Reason of the State, in which Botero argues, against Machiavelli, that a prince’s power must be based on some form of consent of his subjects, and princes must make every effort to win the people’s affection and admiration.

Price: $6,000.00